Lohud; June 18, 2013 By Theresa Juva-Brown and Khurram Saeed

TARRYTOWN — With technical diagrams covering the walls and rows of workers hunched over laptops at portable tables, it’s a world of deadlines and engineering calculations at the headquarters of Tappan Zee Constructors on White Plains Road.

Despite long days, there’s a quiet excitement to the hard effort of designing and building the new Tappan Zee Bridge.

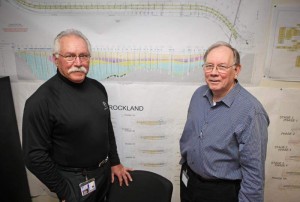

“You can feel the buzz in this office when you come in here, I don’t care what time of day — it’s buzzing,” TZC president Darrell Waters said on Friday during an exclusive sit-down with The Journal News, joined by Walter Reichert, TZC’s vice president. Waters and Reichert are employees of Fluor Corp. and Granite Construction, two of the four companies that make up TZC.

From the project’s $3.9 billion price tag to the pair of 400-foot cranes set to arrive by barge this week, virtually every aspect of the bridge replacement is on a grand scale, including Waters’ attitude about such a challenge.

“I’m a big job guy,” Waters said. “They don’t get any bigger than a big job in New York — it’s like playing baseball.”

The pair of veteran civil engineers also worked on the new World Trade Center, making the Tappan Zee project their second high-profile job in recent years. And it’s not a typical bridge project.

“This one’s from scratch,” Reichert said. “All the way up, it’s brand new. You don’t get very many opportunities in the New York area to do that.”

The colossal undertaking keeps TZC’s top bridge designers and engineers busy 12 to 13 hours a day. The team is so enthusiastic, Waters and Reichert have to remind them that it’s a marathon task, not a sprint.

“It’s five years’ worth of work, so you have got to be careful,” Waters said. “Even though you might want to work 16, 18 hours a day, if you do that, you can’t make it. We have to watch each other’s back.”

“We can’t afford to have everyone burn out,” Reichert added.

How the span will emerge

Construction will be kicked into high gear by next year, with 20 cranes, 60 barges, and two floating concrete batch plants in the river, not to mention the giant Left Coast Lifter, one of the largest floating cranes in the world.

Crews will work in the middle of the river, as well as along both shores. Piles will be driven into the river and the bridge foundations will be placed on top. Columns will then begin to rise from the foundations. Bridge decks will then be placed on the columns.

If all goes according to plan, by late next year residents might even be able to see some parts of the bridge’s towers, which will reach more than 400 feet in height.

To speed construction, some components, such as structural steel, will be assembled at several staging areas along the river.

“If it was a normal bridge you would build everything on site,” Reichert said. “A couple of miles away from here we can pre-fab sections of it. That type of thing helps you cut the time.”

Meanwhile, Hudson Harbor, a townhouse complex in Tarrytown, will be used as a place to load workers onto boats that will take them to the barges, TZC leaders said.

A journey to the river bottom

Because of the unique composition of the ground beneath the Hudson River, the biggest challenge for TZC is designing the bridge’s foundations. Ideally, TZC would lodge all of the pilings deep into bedrock, but only half the bridge, mostly near the Westchester shore, sits on solid rock. Bedrock is about 750 feet down near Rockland and virtually unreachable for bridge builders.

As a result, TZC will rely on friction created by the piles and the surrounding sand and soil to hold up the new spans. Those piles will have to be about 350 feet in length – each longer than a football field – in order produce sufficient friction, Reichert said.

“When you have 300 feet of material above it, even though it may not be all that cohesive or dense, it’s still a lot of pressure on it,” Reichert said.

Starting next month, TZC will install test piles along the bridge’s footprint to determine the length of the piles needed during construction. Recently completed soil testing also provided valuable data about the composition of the soil below.

“So far we don’t see anything different than what we expected,” Waters said. “There’s minor differences but nothing that bothers us yet. The proof of that comes with the test pile program.”

http://m.lohud.com/localheadlines/article?a=2013306170090&f=1166